PRESS

The supremely sticky campus

6:53:54 4 August 2023

50.8229° N, 0.1363° W

The following article first appeared in the August 2023 edition of Education Design & Build.

There’s nothing quite like a global pandemic to upset a director of finance’s circadian rhythms, and perhaps nowhere more so than at a British university – especially one that borrowed to spend millions on bricks-and-mortar projects it imagined would give it the edge in attracting and retaining that holy grail of holy grails: the high-calibre campus-dwelling patron-in-making student. Throw in Brexit, the renewed freeze on student tuition fees and murmurs in government of national and international student number controls and our sleepless finance director’s beginning to look at a change of career.

Thing is, there’s no evidence that a brand spanking new set of buildings – in and of itself – attracts and retains students or results in better work and outcomes. To be clear, it’s not that students and staff don’t appreciate excellent so-called ‘learning spaces’, but rather that they expect so much more of a university, not least a campus life that is more like the most fluid and interchangeable of 24-hour high streets. If we begin, therefore, by broadly agreeing that a decent campus is an ever-evolving place of cultural and social exchange, a marketplace of ideas, an integrated and innovative cluster of all types of learning, then creating the sort of campuses that people love doesn’t have to cost the earth.

For us, that means adopting an approach that speaks to the evolving or ‘always meanwhile’ design of the festival, where the very best programmes are platforms for and invitations to audience participation, and where the focus is as much on people, culture, identity, and technology as it is space. Driven by a vision that includes – but is not limited to – achieving the highest education standards and underpinned by storyboarded or ‘experience mapped’ research, it’s a design that pays attention to, anticipates, and adapts to the needs and wants students across the day, week, month, and even term. It’s designing with time as much it is with space. None of this is to deny the importance of spatial or functional design solutions, but rather to simply champion an experience-led approach, one in which the design is informed by a deep understanding of the people it seeks to serve. It’s an excellent way to avoid falling into the trap of imagining that everything will be solved by a brand new shiny award-winning building. Form follows function follows people – swap these around and it all falls apart.

Taking the low road

Pockets of this kind of experience-led design can be found on all sorts of campuses. For evidence of the counterintuitive success of the cheap, temporary, almost style-less – what the technologist and writer Stewart Brand calls ‘low road’ – university building, then Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s legendary and now finally demolished Building 20 is probably the most remarkable example of unbelievably fine returns on the most modest of investments. A timber structure, Building 20 was designed in an afternoon, took six months to build, and was meant to last as long as it serviced the development of radar during the Second World War.

Loved by university researchers for its easily owned and adaptable nature, and for the fact that it encouraged cross-departmental fertilisation of ideas, Building 20 once housed no less than nine working Nobel Prize- winners. What this building must have meant as a grand attractor to MIT’s student-and-staff recruitment and retention programmes is now impossible to quantify, but it’s almost certainly the most valuable shed in the history of further education. On the other hand, Brand once called its landmark replacement, the Stata Centre, that ‘overpriced, overwrought, unloved, unadaptable, much sued abortion by Frank Gehry’, which is possibly a tad unfair, but you get the idea: starchitects don’t create valuable Building 20-type learning spaces; the people that use them do.

Festivalising the campus

The legend of Building 20, of course, is historic and only one element – albeit a fundamentally important one – of MIT’s campus. For something more current, more comprehensive, and certainly more intentional, Western Australia’s Curtin University’s hard to beat. When in 2011 the Australian architect and urban thinker Andy Sharp arrived to undertake a spatial masterplan for the campus, he quickly discovered that an infrastructure inadequate to the needs of students and staff was the least of its problems. Apart from teaching hours, the campus was empty. ‘At certain times of the day, you could shoot a gun down the corridor, it was that empty.’ It was being ‘managed to death’, a ‘do-nothing-and-nothing-needs-doing’ culture elevating the department of maintenance to chief place maker and manager. Many of the buildings had lost their way, their original functions hijacked, their backs turned on the public realm. Sharp made a case – academic standards, business, and spatial – for the creation of the campus as a ‘fun and exciting experience’.

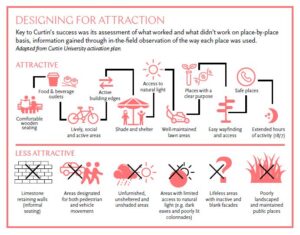

Driven by this beguilingly simple vision, the subsequent Place Activation Plan’s a manual on how to create the supremely sticky campus. Founded on observational research, participatory-user workshops, activity mapping scenarios, a set of values, and an integrated approach to making place, the plan proposed a foundational ‘heart, hive, and home’ identity to create ‘a diversity of choice across a variety of interconnected destinations’. Its centrepiece would be a main street, and a set of brand and design guidelines would be employed to activate it and the rest of the campus, piece by piece. A dedicated Place Management Team would oversee the activation, kicking off with so-called ‘quick wins’ in targeted destinations, the strategy’s success triggering medium- and long-term activations, all of which would come together to create the desired campus ‘stickiness’. Simultaneously, a plan was set in motion to repurpose the campus’s buildings, returning many to their original functions, and ensuring that they served student-initiated activities. Persuaded by the overwhelming success of those early quick wins, a now risk-friendly governance and management approach to place activation would guarantee follow through on planning. The result: a campus renowned for its sheer vibrancy and one that has in a few short years made Curtin University the most popular university in Western Australia.

With many a university searching for ways to better balance the books and continue to attract and retain staff and students, there’s much to learn from an experience-led, festival-like and piecemeal approach to teaming up with participatory-users to create campuses that have the ability to, as we often say, attract, involve, and give a genuine sense of belonging to both students and staff. As an approach, it’s very light on its feet, has the capacity to learn as it goes, and is much the cheaper option when it comes to repurposing boring campuses as supremely sticky – which will please our director of finance.

For the original article, see here. None of the universities mentioned here are past or present clients. The excerpt on Curtin University is adapted from the The Experience Book with the permission of Black Dog Press.

Header image credit: Glastonbury Festival

Building 20 image: As seen in The Experience Book, courtesy MIT Museum

Curtin diagram adapted for The Experience Book from Curtin University Place Activation Plan , 2012