PRESS

Experience masterplanning the future city

9:08:53 27 April 2020

62°19’12”N 9°16’06”E

This article first appeared on the Roca Gallery site.

My most terrifying read of last year was a short article by the author of Ghost Cities, Wade Shepherd, in which he charted the rise of the built-from-scratch city. Driven by unprecedented migration, over half of us already live in urban areas, a number set to increase by an incomprehensible 2.5 billion by 2050. With nearly 70% of the world urbanised, it will need somewhere to actually live. Enter the current frenzy in city building. With over 120 projects taking place in 40-plus countries, it is, as the economist Paul Romer says, the development of, “more urban area in the next 100 years than currently exists on earth.”

Rather than retrofit cities whose infrastructures, utilities, citizens and regulations pose significant obstacles to developers, the preference is for starting afresh, a new and deregulated wave of city building that has resulted in the likes of China’s Khorgas or Malaysia’s Cyberjaya. As well as less complicated, says Wade, this kit-box approach to city building is claimed by its national and regional sponsors as being cheaper and more profitable than attempting something, for example, like the generation-long regeneration of London’s Kings Cross. Quoting anything from $40 billion a pop, the world’s mega-engineers can barely control their reactions. It’s the wild wild east.

As I say, terrifying. Billions of tonnes of concrete, trillions of miles of cabling, and an immeasurable drain on nature’s ailing resources. Even in the reasonably rare event that there’s a genuine market driving their creation, many of these cities aren’t being made to house those in need, but rather—to quote the market literature used to sell in South Korea’s Songdo—aim to provide “the ultimate lifestyle and work experience” to an otherwise prone-to-flight middle class.

Brave new worlds, these cities commonly mistake people for categories of users, and are beholden to the Internet of Things, and to the non-presence of the manufacturing and municipal sectors, industries they categorise as dirty, dangerous or difficult. They zone as one might zone a theme park, and borrow everything—ideas, names, forms—from elsewhere, parachuting in replicas of the likes of Venice’s canals or New York’s Central Park. Terrifying, then, to think that the engineer has turned creative director of this—the biggest community-building exercise in the history of humans.

EXPERIENCE MASTERPLAN FOR MELBOURNE AIRPORT

There is, I believe, another way. If we are to build cities afresh, let’s start afresh. New process, new language: start with people not users. Our needs and wants, to bastardise an architectural jargon, are the underlay of any design project, and not, as is so often the case, the overlay. By which I mean, begin with qualitatively—as opposed to quantitatively—understanding the local, our habits, what holds us together as groups, extended families, believers, and the spaces in which we express that commonality. Rather than engineer behaviour, listen to it. Design—as the urban planner Jan Gehl might say—by beginning with life, not buildings. Start with a programme for the way people spend time, and not, as is usual, the way we use space. Do this and we will build cities that work.

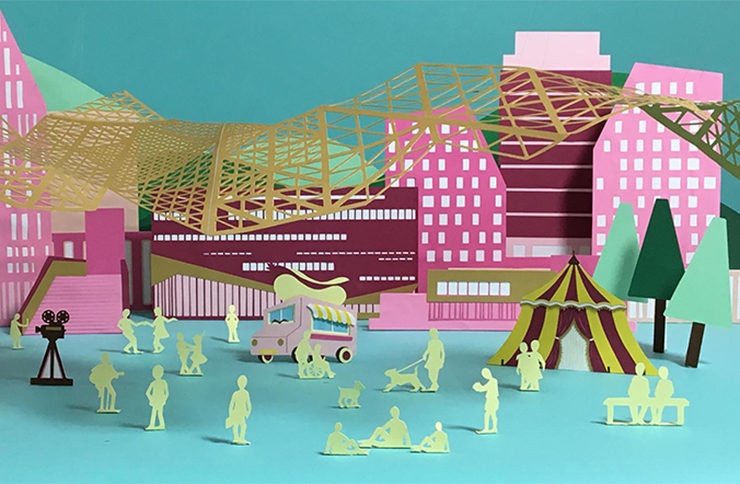

EXPERIENCE MASTERPLAN FOR UNIVERSITY OF BRIGHTON.

IMAGE ANNEMARIEKE KLOOSTERHOF.

All of which is easy to say, I know. However, none of it’s new. “Experience Masterplanning” is the new name for good city making. It’s born of an understanding of what it means to curate—or care—for humans. It finds its modern antecedents in the notion of the campus, and in the innovation hub as championed by the likes of MIT. For the thinking behind it, few books delight more than Christopher Alexander et al’s A Pattern Language: Towns, Buildings, Construction of 1977, which speaks about architecture and urban living, and which argues—by means of hundreds of hypothetical (and inherently flexible) design solutions—that people “should design their homes, streets, and communities.” It says that the most “wonderful places of the world were not made by architects, but by the people.” The $40 billion city-in-a-box is not, whatever its marketing hyperbole, these wonderful places.

Architects and engineers, of course, are also people, and A Pattern Language is really a love letter to these professions. It says—along with all advocates of experience design—that we must temper our love for universal principles with an understanding of real need and real want. It says that form may or may not follow function, but never at the cost of people. It says design cities for good economic reason, design them with people, and design them, therefore, so that they go beyond the efficient and effective genius of the engineer. Design open, mixed-design, porous, cradle-to-grave neighbourhoods. Design for the impoverished, the struggling, the challenged. Design houses for multiple generations—flexible, self-adaptable living spaces. Design for the public, for civic involvement, for shared experience. Design for amenities that are permanent, semipermanent and transient. Design for a green future. Do this and we masterplan cities informed and run by the rituals of people, which develop—from the bottom up—their own myths, and that attract, involve, and give people a genuine sense of belonging.

Image credit: San Francisco Bay by Hassell and University of Brighton by Annemarieke Kloosterhof.